The Fire of Now: On Spiritual Activism, Leadership, and Contemplative Practice

An Interview with Darnell Moore

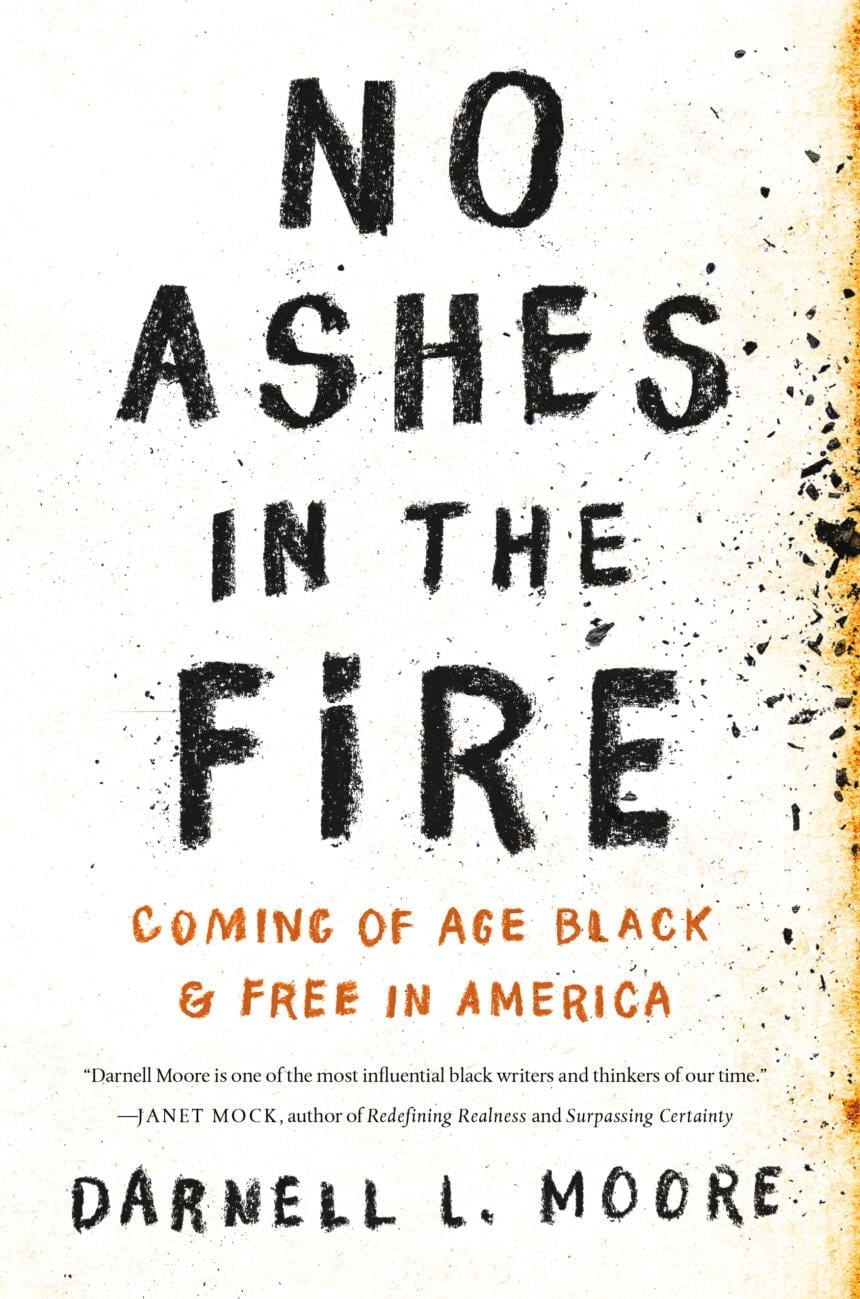

By Jenara NerenbergDarnell Moore is the author of No Ashes in the Fire, a coming of age memoir of spiritual and LGBT activism. At the core of Moore’s story is a devotion to truth, excellence, and community-building. We learn about Moore’s coming out as gay after being immersed in black Christian churches and how he took his spiritual values with him to local politics and ultimately to academia and community organizing in Ferguson as part of the Movement for Black Lives. Moore is now co-managing editor of The Feminist Wire and Writer-in-Residence at the Center on African American Religion, Sexuality, and Social Justice at Columbia University. We spoke with him about his new book and his thoughts on leadership and spiritual activism.

Jenara Nerenberg: Looking back at your history in the Christian community and your current LGBT activism and work in the Movement for Black Lives, how would you define spiritual activism and what does it mean to you?

Darnell Moore: Another way to frame this work is thinking of it as an attempt to bring about transformative justice in the world. I understand that as a spiritual practice. All forms of activism committed by those who are interested in creating a more just, a more loving, a more liberatory, and more equitable world—to me, the undercurrents of any movement like that, of any work like that, is spiritual at heart.

That is different than religious, which is shaped by one’s participation in or commitment to institutionalized religious practices. I mean “spiritual” in the sense that it is about a greater good, connected to the essence of humanity, essentially the larger community that connects all of us. So, in that way, I don’t know if I would make a distinction between spiritual activism and activism writ large, because I see activism as a spiritual act anyway.

Jenara Nerenberg: What do you think this particular moment in time is calling forth, in terms of spiritual activism within the Black community?

Darnell Moore: I don’t know if this is within the Black community—or maybe these are just my thoughts about organizing or activism or spiritual activism in general. We often think that a big part of the work is naming and then ameliorating the conditions that are impacting people in the world by either oppressing violently, limiting people’s potential to live and/or to live livable lives, right? But I think the spiritual aspect of it, if there is to be one, is also about self-reflection and analysis. That is, understanding that the way that we have to undo this sort of stuff—the, dare I say—“monsters” within ourselves. It’s easy to name the targets that we want to impact, that we want to raze, right? But it’s harder to do the work of analyzing and thinking about the way that any of us individuals can be implicated in harm or can be implicated in injustice—that’s the harder work.

It’s really easy to talk about structural change, because often when we talk about racism, sexism, and antagonism against queer and trans people and xenophobia, these sound like big forces that we distance ourselves from. At the core of what I understand to be a radical approach to transformative justice is understanding how any of us can be both victims of oppressive structures and also victimizers. That is whether we are aware of complicity in those structures or not. Then any one of us can have our feet on somebody’s neck, as much as the oppressive systems can have their feet on ours. I think that that is, to me, the spiritual impact of the work.

Jenara Nerenberg: Along those same lines, in the book you talk about practicing critical self-reflection and I wanted to ask about your thoughts on contemplative practice. What does it look like for you to practice critical self-reflection? Would you consider that a contemplative practice?

Darnell Moore: I think it is one. It is a contemplative practice, because it requires deep insight and study. Studying, to me, is a contemplative practice. That is, reading the world, analyzing what’s happening in the world, being fully aware—and by “world,” I don’t just mean our own sort of small world that we exist in, either with relative safety or not, but the worlds of so many other people. That requires an attentiveness to what’s going on around us and/or not around us, in spaces outside of the geographies that we call home or that we call communities.

Another part of that then is also deep reflection, which is akin to meditation, too. I see reflection and meditation as sort of connected, although they’re different. And what I mean by deep reflection is really giving thought and empathic regard to the sort of lived experiences of other people, to the way that the world or the state or individuals or groups, religious bodies, whoever, might enact injustice, but also the way that those things happen as everyday practices in our lives.

What I do want to say, though, is I don’t want to talk about this work as if it’s only about enacting outward. I think that there is work that is required inward, too, and meditation then is part of that—meditation, prayer (if that’s what people do), quiet, solitude, and community—engaging in community, communal practices, whether that’s thinking about other means of healing work via yoga, the movement of the body, physical exercising, running—all of those things are all connected: the mind, the body, the spirit are one.

So, for me, one can’t do the work of acting as an activist or trying to bring about justice without also attempting critical thought and reflection, without also creating spaces for meditation and the type of bodily care and spirit care that all of that work requires.

Jenara Nerenberg: Absolutely. And when you were sitting down to write the book and share your life story, was there a particular intention that you were sitting with as you were narrating and writing the book and sharing your journey?

Darnell Moore: Yeah, there was. My intention, or at least what I imagined, was an audience that I was writing for, and that audience was comprised of like 16-year-old me. Honestly, that’s who I was writing to. I was writing the words that I felt I needed and didn’t have, words that could have helped me to embrace myself: my full complexity as a black boy becoming a man, at least how society tells us what manhood is supposed to be; as a queer person; as a spiritual, religious person. I was writing that book for that young person who needed access to other ways of being.

Darnell Moore: Yeah, there was. My intention, or at least what I imagined, was an audience that I was writing for, and that audience was comprised of like 16-year-old me. Honestly, that’s who I was writing to. I was writing the words that I felt I needed and didn’t have, words that could have helped me to embrace myself: my full complexity as a black boy becoming a man, at least how society tells us what manhood is supposed to be; as a queer person; as a spiritual, religious person. I was writing that book for that young person who needed access to other ways of being.

That was the intention I set. Some practical things I did, like I called upon ancestors to really sit with me, to help me to think through the story, everything, from like what stories to share, to what commentary I might provide on those stories. I prayed. I prayed a lot. I prayed not only for the purpose of getting the book done, but I prayed for myself through the process, like for patience and for clarity, for the strength to be honest, integrity, and for the right words that could fall at the right time before an audience who might be able to receive them.

Those were sort of some of the things that I committed to during my writing time, as practices.

Jenara Nerenberg: I felt all of those things, and it was really beautiful to witness. Can you talk a little more about the “spiritual undercurrent and the radical black love that flowed” the weekend you spent in Ferguson and that perhaps continues to flow currently?

Darnell Moore: Absolutely. I’ll say that while much has been written about the Movement for Black Lives with regard to the sort of spectacular displays of resistance and disruption, that it’s like everything—the media pays attention to the protests, the disruption, and political candidates on the stages who had either refused to say something like “Black lives matter” or refused to adequately address the concerns of organizers across the country.

Books have been written and analyzed connecting this contemporary movement iteration to a long-standing struggle for Black liberation in the country. Much has been written about policies, and/or what people thought were lack of policies, although the Movement for Black Lives roundtable came out with this policy agenda.

At the time, less had been written about what I understand to be the more existential, deeper spiritual elements of the movement, which is not only elements that I think were present within this iteration, but always present within the Movement for Black Lives and the struggle for Black liberation in this country and across the globe.

At the the core of it is this sort of notion of love, of radical love, which, to me, brings to mind justice—which, to me, brings to mind notions of peace. Peace that can only come via justice. People who can only come with the type of love—and, for me, I define love as the energy that removes the distance that exists between us and the other.

So many of our policies and practices are unloving because they’re about creating separation, creating vast separation between those with wealth and those without, between those who sort of conform to the ideas and structures of society, whether that’s around gender, sexuality, or so much else. It’s all about hierarchy. It’s not about the bringing together of a people.

The Movement for Black Lives was all about the bringing together of a people. The movement would be one that was about a people who love Black folks and this country, enough to be honest about its atrocities and to call into account. That, to me, is an act of love. It was about the sanctity of life and the lifting up of life, and our right to live and not be either killed or slain by law enforcement, or the practices that come by virtue of economic disenfranchisement and political disenfranchisement.

It was about a calling to life, a calling to account that Black people are human and deserve to be here. That, to me, is such depth—it was about community, collectivity, and coalition. The sort of everyday-ness of it wasn’t spectacular stuff that we see on TV. It is about the stuff that you don’t see, like people within these collectives who, outside of a camera, were making sure that other folks had beds to lay in if they lost jobs while protesting over the course of 100 days, like they did in Ferguson, and that they were eating.

My father passed when I was writing the book. There was a Black Lives Matter New York City chapter that showed up, from two hours away, to Camden, where we funeralized him. They came from New York all the way to South Jersey without me telling them to. I looked over, and there they were at the funeral home. That’s love. That, to me, is an example of the spiritual nature of the movement that so many of us missed and didn’t account for.

Jenara Nerenberg: And do you have a particular message or take-away you hope readers will find when reading the book?

Darnell Moore: I think that there are several messages for readers, from wherever they’re reading the book, from whatever standpoint that they’re reading it, that they could take away from it. One is a message about the importance of radical love, or, what I’m calling it in the book, “radical black love.”

It’s really a history about my family, too, who was my first example of what love looks like. I come from a family that did not dispose of its people. That practice informed my political viewpoint. There’s that. There’s the notion of non-disposability, this notion of deep community and a commitment to community building.

The book title, No Ashes in the Fire, is a reference to a story about an incident where I was nearly set on fire as a kid, but it really is a metaphor for the bible, what it means for any of us who exist on the edges of margins to find ourselves, almost daily sometimes, at risk of being set ablaze—metaphorically and sometimes literally—by a variety of different violences.

The message really is that some of us survive not without the support of those around us, but some of us don’t. The survival, and the lack of the survival, implicates all of us—the readers, the writer (myself). I try to be as honest about my own implications in these as possible.

And it’s a call to action that we all are holding some version of gasoline in our hands. It’s up to us to not utilize that to harm, to light the match, to set someone’s potential for well-being, for life, for happiness, for peace, to sort of set that on fire.

Jenara Nerenberg writes and speaks widely and is the producer of several author initiatives for The Neurodiversity Project, Garrison Institute, and the UC Berkeley Greater Good Science Center. An Aspen Ideas “Brave New Idea” speaker, her work appears at Fast Company, Susan Cain’s Quiet Revolution, and elsewhere. You can find her on Facebook and Twitter.

Photo courtesy of Erik Carter