Finding Stillness in New York City

An Interview with Bill Hayes

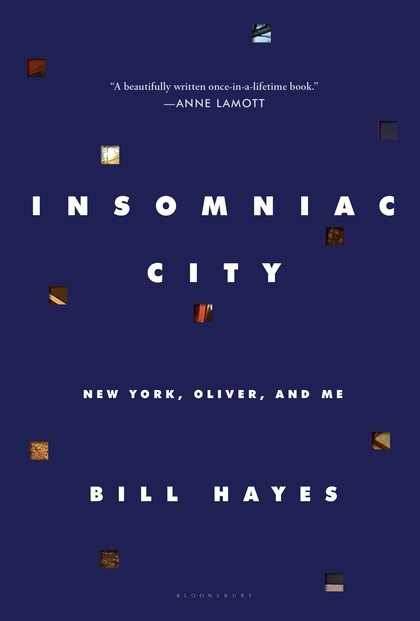

By Jenara NerenbergPhotographer and author Bill Hayes’ most recent book, Insomniac City, is a memoir about his partnership with the belated Oliver Sacks and set in his beloved New York City. Like Sacks—who is one of the greatest contributors to our understanding of the brain and neurodiversity—Hayes is a keen observer and documenter of his fellow human beings. When Sacks and Hayes fell in love in New York City, it was Sack’s first time at the age of 75.

We recently met with Hayes in San Francisco to discuss the journey of making the book and the stories and photographs that constitute its quiet, meditative passages. There’s a palpable stillness to Hayes’ prose and pictures—and in his reflective conversations with Sacks.

It felt like your book was very spiritual in nature, without your explicitly saying that it was. I felt a stillness and calmness in how you approach each person you meet. Can you speak to that?

I think I have more of a scientific orientation rather than spiritual, but definitely an intense relationship with nature, even with nature within a big city like New York City. I find my own ways to meditate and contemplate, whether it is on a subway ride or while swimming. I think one can practice contemplation outside of, say, a yoga studio. You can have an awareness of your fellow human beings while just taking the subway, and I think that is what comes through in Insomniac City. It’s about paying attention, being respectful, and making connections with fellow human beings.

I think I have more of a scientific orientation rather than spiritual, but definitely an intense relationship with nature, even with nature within a big city like New York City. I find my own ways to meditate and contemplate, whether it is on a subway ride or while swimming. I think one can practice contemplation outside of, say, a yoga studio. You can have an awareness of your fellow human beings while just taking the subway, and I think that is what comes through in Insomniac City. It’s about paying attention, being respectful, and making connections with fellow human beings.

I wanted the book to have a spareness to it, to have lots of white space. In the text passages, book design, and photographs, you almost get the impression of passing anonymous strangers in the street. But I don’t tell the stories behind the pictures, except for one or two. I wanted the reader to have the feeling of being in New York. With the white space surrounding the photo or journal passage, I wanted to encourage the reader to take some time to reflect on their life or think back on experiences they might have had. I like the idea of people taking their time with the book and letting it stretch out their experience of time and memory.

I definitely felt that. For example, you’d have an empty page with just a couple of lines of dialogue between you and Oliver Sacks. It was like being there in the room with you.

That came organically from my journal. In May of 2009, shortly after I moved to New York, I already knew Oliver Sacks, and we were just getting better acquainted. He said to me one day, “You must keep a journal!” And I wrote that line down on a torn scrap of paper, which read, “5/9/09 O: You must keep a journal.” Oliver was known as a great journal keeper. He kept journals throughout his life, starting from boyhood. I had never been much of a journal keeper, but thankfully I followed his advice—although not very methodically. It was mostly scraps of paper and backs of envelopes that I stuffed in a drawer where I kept them. But in the lead up to this book, after compiling the different notes and transcribing, the diary made up 750 pages.

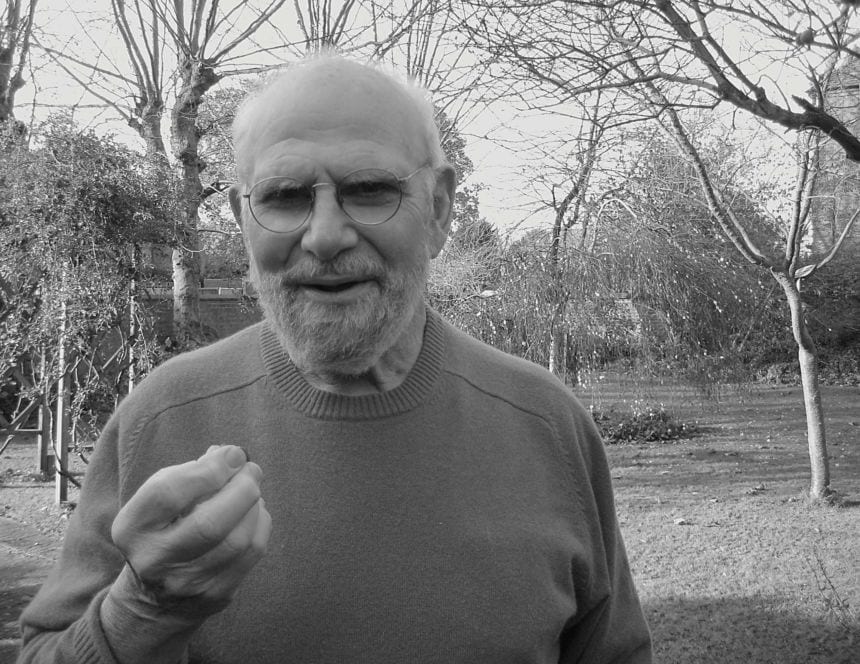

Oliver Sacks | Photo courtesy of Bill Hayes

Does taking pictures feel like a way of meditating for you?

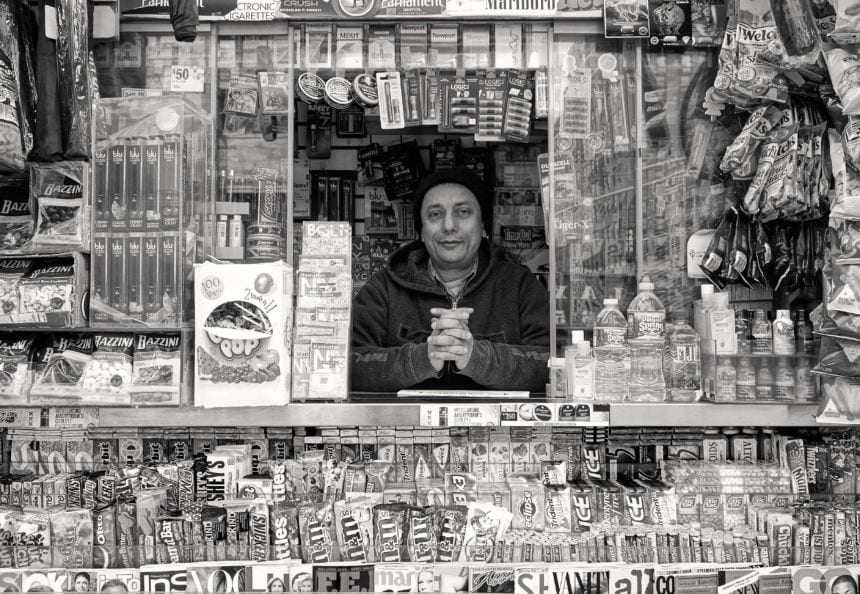

The first word that comes to my mind is “intentional.” When I have my camera with me, there’s a sense that I’m looking for pictures. Often with my pictures, I feel like they’re just waiting there waiting for me to come and take them. My pictures are mostly of everyday people—a man sitting in the back of his truck or a woman in a doorway. All it took was for me to see them in that moment, in their humanity.

It’s very important to me to ask for their permission, because there’s a kind of trust that the subject places in you, the photographer. So I always ask, “Can I take your picture?” Even still, the pictures work best when there’s a kind of un-self-consciousness, openness, trust, and intimacy on the subject’s side. That can happen even in an immediate, anonymous encounter. It’s been a way for me to get to know New York and New Yorkers.

What do you think New York and New Yorkers have to teach the world right now, in this time of political and cultural uncertainty?

A lot. When you live in New York, you have to live with very different people in a very geographically compressed place. New Yorkers, as rough around the edges as they may be, take care of one another and watch out for each other. I once saw a woman faint in a very hot subway station, right at the edge of the platform, and, before I could even get to her, two or three people came to her aid. It was such a beautiful thing to see. One of them turned out to be a doctor and made sure her head was protected, and he signaled to someone to get water. And then there was this other person who was just this calming presence, holding her hand.

I just think it’s so important to get to know your neighbors and respect them. That relationship is so underrated. People are starting to recognize that they need to stand up for their neighbors, friends, and those who don’t have a voice.

Sam at his Newsstand | Photo courtesy of Bill Hayes

The feeling of empathy really stood out to me while reading your book. Can you speak to that?

I think I have a deep well and strong streak of empathy. Some of it is by chance, but it’s also because I was raised among many women. I had a wonderfully empathetic and artistic mother and five sisters, who are all very sensitive, artistic, empathic people. It’s a huge part of who I am and something I shared in common with Oliver. Because he was approaching people as a neurologist, he was especially drawn to those with neurological disorders that made them feel like they are outside of culture and society. His amazing empathy allowed a kind of recognition of their humanity. You see that throughout his writing.

Did you and Oliver talk much about the topic of neurodiversity?

It was less a topic of conversation and more about seeing Oliver interact with people with different traits. Oliver was completely unfazed and his example calmed those around him. You just let people be who they are and be with them as they are. We’re all different, which is healthy, and you don’t need to do something to elicit a different type of behavior when you accept that fact of difference and that we all have different roles to play.

Jenara Nerenberg is a writer and journalist, whose coverage of neuroscience, innovation, and wellbeing regularly appears on outlets including Susan Cain’s Quiet Revolution, the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, and Fast Company. Find her on Twitter here.

Photographs courtesy of Bill Hayes

What a lovely glimpse into Bill Hayes mind, his photographs and his relationship with Oliver Sachs. So human, so unguarded. Everyday, yet inspiring. Thank you for sharing this. I write a journal (disorganised like Bill Hayes’) and take lots of photos of my mother who is living with dementia. This piece made me think….