Solitary Encounters

Making Our Selves and Our Stories

By Jennifer Stittare we creators in fact

or collectors of relics:

do we make grow

or cast into stone?

—A. R. Ammons, “Tape for the Turn of the Year” (1965)

Every story has a beginning. This one began with silence—with the awful absence of sound and Herman Melville’s fear that he might wander over the edge of the abyss only to find depravity in his accursed quietude. It began, too, with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s mute mastery of man’s transcendence, Henry David Thoreau’s soundless sea of deep contemplation, and the countless unnamed solitary seekers who sat still for a wise and noiseless moment, dared to listen to their innermost voices, and heard the unspeakable.

Every story has a beginning. Mine begins, too, with silence—with being silenced. My voice was smothered and squashed for years by a violent mother whose anger and bitterness consumed her, whose anger and bitterness very nearly consumed me. As a young girl, my only desire was to vanish from the world, and I did by disappearing into the stories printed in books. I devoured books. I wandered alone into strange worlds where friendship and love were real possibilities; I discovered good worlds that offset the gloom of my own, worlds where the darkness didn’t always defeat the light; I learned about free worlds where people spoke and had companions who heard them.

For years, I sojourned deeper and deeper into myself. But I realize now that all those hours spent alone reading were also hours spent sauntering out and down far-flung paths, roaming beyond the boundaries of my narrow reality, where I could imagine other, different, and better ways to live. Books were miraculous doorways that opened out and into the lives of others. “Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other’s eyes for an instant?” Henry David Thoreau exulted in Walden (1854), one of the books that buoyed me with a sense of hope, wonder, and empathy in my intellectual infancy.

For years, I traveled alongside solitaries, seekers, monastic mystics, freedom fighters, poets, theologians, theorists, and thinkers. I drank their words as a pilgrim stranded in a desert would drink water: fervently, greedily, frantically, and gratefully. All that time, I had been studying and practicing solitude, but I didn’t know it. Not yet. I wouldn’t recognize that until much later, on a particularly sunny and unseasonably warm September day during my third year of graduate school when I decided to get up from my desk and go for a walk.

* * *

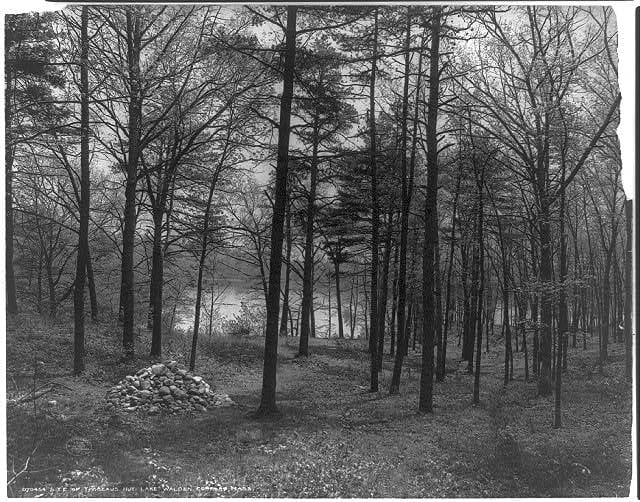

Thoreau’s cove, Lake Walden, Concord, Mass., c. 1900-1910. A view of Walden Pond, where Thoreau lived for two years, two months, and two days from 1845-1847, photographed approximately forty-eight years after his death.

On January 14, 1853, Henry David Thoreau recorded a melancholy observation in his journal: “The bones of children soon turn to dust again.” During the frozen winter months, Thoreau’s thoughts were often occupied by death, and his January journals are especially riddled with these images of decay. Five days earlier, on January 9, he recounted a stark, bleak, and eroding landscape: “I heard from time to time the sound of stones and earth falling and rolling down the bank in the cuts. The earth is almost entirely bare.” On January 21, he recorded a nightmarish passage about depravity: “Yesterday I was influenced with the rottenness of human relations,” he wrote. “In the night, I dreamed of delving amid the graves of the dead, and soiled my fingers with their rank mould.” For many of us, January is a time of reflection and contemplation. As each new year begins, we collectively pause to take stock of our lives, of what we said and did during the past 365 days, and we resolve to refine our selves and alter our actions. For Thoreau, too, January was a meditative month. But it was also a month of mourning, of longing to once again converse with the dead. Eleven years after his older brother John’s death, Thoreau still sometimes succumbed to his sadness—as he would every January for the rest of his life.

* * *

On New Year’s Day 1842, John Thoreau nicked his finger while stropping his razor. He was twenty-six years old, and he didn’t think a thing about it. A few days later, though, he noticed that his finger had begun to throb. And a few days after that, it began to look gangrenous. That’s when he collapsed, convulsing, on the doorstep of his family’s home. He had contracted tetanus, or “lockjaw,” and he suffered from excruciating spasms for nearly three days. On the afternoon of January 11, John died in Henry’s arms.

Henry’s grief very nearly consumed him. A week after John’s funeral, Henry’s private heartsickness finally overwhelmed his mind and his body, and he suffered for several days from psychosomatic convulsions—a disease that can only be described as pseudotetanus. For several weeks, he found himself unable to write, incapable even of jotting a quick line in his journal. Finally, on February 19, he noted, “I begin to see how that the preparation for all issues is to do virtuously.” The seed that would blossom into two years of deliberate and ethical living at Walden Pond had been planted. The next day, he mused that “the death of friends should inspire us as much as their lives. If they are great and rich enough, they will leave consolation to their mourners.” Each entry was an elegy for his brother, a lament, perhaps, but not one without hope or gratitude. “How can any good depart? It does not go and come, but we,” he concluded. On the February 21, he described his disorientation: “I am like a feather floating in the atmosphere; on every side is depth unfathomable. I feel as if years had been crowded into the last month.” His soul and body, he said, had split into “two” that “should walk as one.” On February 23, a brighter light glimmered inside the caverns of his mind: “Every poet’s muse is circumscribed in her wanderings,” he declared, “and may well be said to haunt some favorite spring or mountain.”

Every story has a beginning. This is Henry’s: after his brother’s death, he began to wander. He was spiritually and psychically lost, and he fled to Walden Woods to try to write. He gradually found his way back to himself and, in a way, back to his beloved brother John—slowly, meanderingly, through the art of walking. In 1849, he developed a new daily routine: in the mornings and evenings, he dedicated himself to reading, and he read everything from scientific papers to Greek poetry to Chinese philosophy to Hindu scripture. The afternoons were for walking, for looking, for paying attention, and he often spent more than four hours a day lingering in the Concord landscape, measuring, recording, and collecting its many riches. He went out into the wilderness in search of his muse, and he found it, famously, in nature. The “fertile and eloquent” silence echoing through the Massachusetts woods reverberated through Thoreau’s body and soul with each sauntering step. He observed the flora and fauna, eulogized fallen trees, stalked chipmunks, and spied on sparrows. “What bird wilt thou employ / To bring me word of thee?” he asked of his brother’s spirit, of the majestic hawks that flew far above Fairhaven Cliffs. Thoreau stumbled toward finding his voice and his vocation, and, eventually, from 1850 until his death in 1862, he would come to record very nearly every step, every sight, every sound, and every wild, wondrous miracle in his journal. He was living and writing a philosophy of pedestrianism.

Site of Thoreau’s hut, Lake Walden, Concord, Mass., c. 1908. In Walt Whitman’s 1882 book, Specimen Days, he remembered visiting Thoreau’s grave at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts, before making a pilgrimage to Walden Pond, writing: “I got out and went up of course on foot, and stood a long while and ponder’d. . . . By Henry’s side lies his brother John, of whom much was expected, but he died young. Then to Walden pond, that beautifully embower’d sheet of water, and spent over an hour there. On the spot in the woods where Thoreau had his solitary house is now quite a cairn of stones, to mark the place; I too carried one and deposited on the heap.”

***

Hundreds of feet above Birmingham, Alabama, where I live, there is a paved walking path, an asphalt trail carved into the side of a mountain. Much of the plant life along the path is kudzu, a pestilent yet enchanting and verdant vine that has overtaken much of the mountain’s flora. Thankfully, the trees still protest the kudzu’s murderous shade, stretching up toward the sunlight: wise old oaks, yellow poplars, sycamores, mockernut hickories, and, on the road up the mountain, a lone persimmon tree. The animals are abundant, although I mostly pay attention to the birds: eastern towhees, chipping sparrows, mockingbirds, starlings, tufted titmice, Carolina chickadees, red birds that blend in with the red rocks, and, during spring and summer, indigo buntings more brilliantly blue than any cerulean sky you could ever imagine. The path is a pocket of wildness—in the city but not of it—and is a place of refuge where urban flâneurs can momentarily escape the crowd of the city and find some solitude in the woods.

Vulcan Trail, Birmingham, Alabama, September 2017. The Vulcan Trail is a paved mile-long walking and bicycle trail built into the northern slope of Red Mountain in Birmingham, Alabama. The main trail overlooks the city and is handicapped-accessible.

Kudzu-covered trees (L); Staircase to a Southside neighborhood (R). Kudzu covers much of the mountain’s flora, preventing erosion but also slowly strangling decades-old trees; many of the homeowners and apartment-dwellers who live directly below the Vulcan Trail have built staircases that ascend the side of the mountain to access the main path.

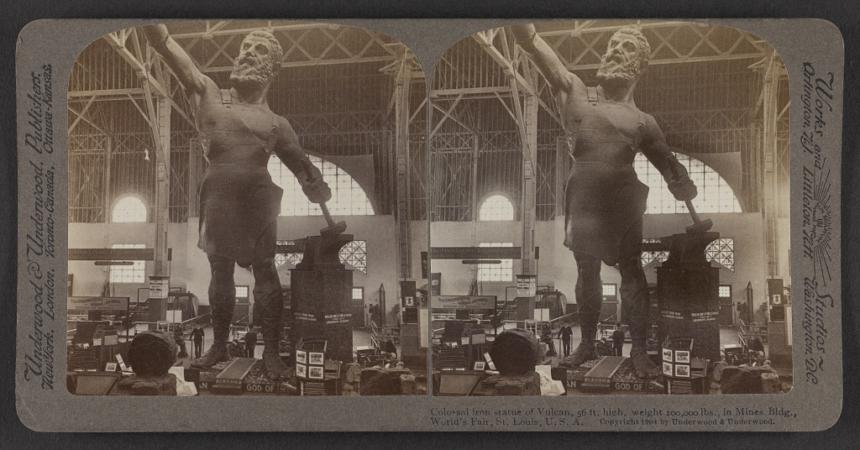

The trail is hewn into Red Mountain, which is named for its red rocks, for its mineral-rich Silurian strata that jut out and up from the earth. Hundreds of years ago, Native Americans used the hematite iron ore to dye fabric rust-brown and to paint their bodies and horses crimson during times of war. At the turn of the century, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, after the city was founded, those same red rocks transformed Birmingham into an iron- and steel-producing industrial hub. The trail itself, Vulcan Trail, is named for the Roman god of fire and forge—and a fifty-six-foot-tall cast-iron statue of that magic metalsmith watches over the mountain, the largest cast-iron statue in the world.

On a particularly sunny and unseasonably warm September afternoon, I suddenly abandoned the rickety, coffee-stained, knife-scuffed butcher’s block table that serves as my writing desk, and I walked out of my house and up the road to the mountain and onto the trail.

Colossal iron statue of Vulcan, 56 ft. high, weight 100,000 lbs., in Mines Bldg., World’s Fair, St. Louis, U.S.A., c. 1904. Vulcan was commissioned in 1904 to represent Birmingham—a manufacturing city founded in 1871—at that year’s World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. Sculpted by the Italian-American artist Giuseppe Moretti, Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and forge, reflected Birmingham’s power to transform her natural resources into iron and steel, booming industries during the early decades of the twentieth century. Today the giant Vulcan statue sits atop Red Mountain, towering over the Magic City, and he has his own park and museum.

That September, walking was on my mind. I was writing an essay about the history of walking, and I had been religiously reading Thoreau’s Journal; like Thoreau, I took up my pen and made obsessive observations in my own notebook about his perambulations. I had been working at my desk for several days when it struck me that I hadn’t been for a walk in a while. And so out I went, one foot in front of the other, to the road up the mountain and onto the trail.

This is where the story gets difficult, the terrain a bit rocky. For most people, walking comes naturally. It’s as easy as breathing. We walk all the time. From the car into the market; a few blocks from the office to the Indian place for lunch; around the corner to the cozy coffee shop; down sidewalks, through parks, up hiking trails. But that September, I was recovering from a long illness, and walking any distance at all without collapsing had become a luxury. I didn’t know whether I could clamor up the slope of Red Mountain and make it onto the Vulcan Trail. But I tried, and I did.

What called me to the mountain that day? Perhaps it was Thoreau’s spirit. I had always felt a spiritual affinity for his writing. I had always been especially struck by Henry’s love for John and saddened by his sorrowful, elegiac journal entries. And it was true that Thoreau’s grief hit me harder this time around. No longer a child, I, too, had suffered losses; I, too, had lost myself; I, too, was a feather floating through unfathomable depths. My mourning was for a lost self rather than a lost sibling. It was an invisible despair, but it was another kind of grieving nevertheless, a camouflaged grief for an altered body and all the lost possibilities that accompanied my chronic illness—exotic foods never to be eaten, far-away places never to be explored, children never to be born. Or perhaps it was simply stir-craziness, and my body and mind united in that moment to demand a bit of sunlight and fresh air.

A wild trail in September. Above and beyond the main paved trail are dirt paths and untamed passages for more adventurous explorers. These secret routes are swampy and nearly unnavigable during the summer months but are slowly transformed into traversable tracks as the foliage falls away during autumn and winter.

This essay is supposed to be about encountering solitude, and it is. But first I had to walk slowly back to myself before I learned how to recognize solitude, before I learned how to genuinely practice it with an open and loving heart. I had to wander down many lonely, isolated paths that turned out to be painful dead ends. Walking, Thoreau wrote, allows us “to be able to see ourselves, not merely as others see us, but as we are.” What I discovered was this: solitude requires courage, and it demands that we wrestle with our weaknesses as well as our strengths, that we be present in our bodies and our minds before we can awaken to the world and inner peace. After John’s death, Henry walked, and walked, and walked. He walked until he saw himself as he truly was, until he could truly hear his innermost voice, and he kept on walking for the rest of his life. But the project wasn’t walking itself. The project, I realized, was what walking allowed Thoreau to do: to be attentive to the world, to be present in both body and mind, and, ultimately, to think.

* * *

There’s a famous passage in Walden that has been so often quoted that it has become a kind of cliché:

The millions are awake enough for physical labor; but only one in a million is awake enough for effective intellectual exertion, only one in a hundred millions to a poetic or divine life. To be awake is to be alive. . . . We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep. I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor. . . . Every man is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour.

In spite of Thoreau’s haughty tone, this is a profound and illuminating insight: Our capacity for deep, contemplative thought is what makes us human. Thinking—conversing with ourselves and evaluating what it is that we say and do—is what cultivates our consciences and makes us moral beings. And yet too many of us sadly sleepwalk through our lives, endlessly distracted by our smartphones, or by the latest app or game or gadget. If we cannot keep company with ourselves, we cannot keep company with others.

* * *

The poet A. R. Ammons once asked whether we are “creators in fact / or collectors of relics.” It is a particularly poignant query for a historian, but it’s an important question for all of us. Are we makers or are we collectors? Are we artists, or passive curators of the artifacts of our lives and our worlds? “The earth and leaves are strewn with pearls,” Thoreau once observed during a walk in wet weather. He collected those pearls, stored them away in his journals, and arranged and re-arranged the way they were displayed in his books. And yet he made something: he sought solitude and made a thoughtful life. He threw off the chains of conformity, and challenged himself and his neighbors to forge stronger friendships and to build more democratic communities. Thoreau’s daily pedestrian practice reminds us that we, too, are also storytellers—that each unique, unexchangeable person has her own story to tell—and that each of us has the power to choose which path to walk down and the power to choose to tell a different story.

Every story has a beginning, and the telling of those stories is in fact an act of communion. Stories are where we think ourselves into another person’s experience, where we live—even if only for a fleeting moment—another person’s life, and where we dwell in our dreams together. As James Baldwin put it in Nobody Knows My Name (1961), “The questions which one asks oneself become one’s key to the experiences of others. One can only face in others what one can face in oneself. On this confrontation depends the measure of our wisdom and compassion. This energy is all that one finds in the rubble of vanished civilizations, and the only hope for ours.”

In 1968, Hannah Arendt wrote that “storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it,” that “it brings about consent and reconciliation with things as they are.” We begin and end with stories, and if we are awake and maybe a little bit lucky, we discover that we have the capacity to tell our stories to others, and that we have the capacity to listen in turn to stories that we would never otherwise imagine. That is our great human potential and the source of our hope, our infinite expectation of the dawn.

Every story has a beginning. And each beginning is above all an act of imagination and an act of creation. Out of nothing we bring something into being. Or perhaps, rather, out of something—some hitherto unspeakable experience, some hitherto incommunicable kernel of truth—we dare to speak words to strangers that we ordinarily wouldn’t say aloud even to ourselves. Those stories guide us out of the darkness, remind us of our own extraordinary power to hope, to think deeply about our political and moral worlds, to judge what is right and wrong, and to take deliberate action in the public sphere.

Every story has a beginning. What’s yours?

Jennifer Stitt is a historian of modern American thought, culture, and politics who earned a B.A. and M.A. in history from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She’s working on her Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She lives and writes in Birmingham.

This is fifth installment of a five-part series on solitude by Stitt. Read the first installment here, the second installment here, the third installment here, and the fourth installment here.