City of Compassion

An Interview with Mayor Greg Fischer

By Tish JenningsLouisville Mayor Greg Fischer is a leader in the compassionate cities movement. The Compassionate Schools Project is a result of his vision and leadership. It is the most comprehensive study ever undertaken of a 21st century health and wellness curriculum in an elementary or secondary school setting. My colleagues and I at the Curry School of Education and the Contemplative Sciences Center at the University of Virginia in partnership with Jefferson County Public Schools are developing and testing this new curriculum designed to promote the integrated development of mind and body. The project interweaves support in academic achievement, mental fitness, health, and compassionate character. —Tish Jennings

Tish Jennings: In 2011, you signed a resolution leading to a multi-year Compassionate Louisville campaign, making Louisville an international compassionate city, the largest city in America with that distinction. What does compassion mean to you personally, and why have you given it such a prominent place in your vision for the city?

Mayor Fischer: My background is that of an entrepreneur and businessperson. When starting a business, I always felt that the most important thing is to do is to decide on the values that are going to be guiding the business. So when I became mayor I asked, “What are the values of the city going to be that I’m going to espouse?” I wanted to communicate those values during my inaugural address since that was the first time I was going to be able to speak to the city as its mayor.

The first two values were easy for me to articulate; the first was life-long learning, and the second value was health—physical, mental, and environmental health. For the third one, I wanted a word that communicated “we’re all in this together” or “we’re all interconnected and the purpose of us is to lift each other up.” I remembered the purpose statement that I had created for the businesses that I ran, which was “Business exists to optimize people’s human potential.” I kicked around a few different words that could try to summarize all those ideas, and Christy Brown was in that particular conversation with me. Christy is an International Trustee of Religions for Peace, the world’s largest International Interfaith organization. She turned to me and said, “It’s compassion.”

Most people think of compassion as empathy and the relief of suffering. I view it as something more proactive. Empathy is a gateway to compassion, but I’m looking for more of a result coming out of that. That’s why I define compassion as respect for all of our citizens, so that we want their human potential to flourish and thrive. It requires action to do that.

Jennings: Why Louisville? How did the city get involved?

Fischer: I rooted my understanding of compassion in Thomas Merton’s epiphany that happened in 1958 in our downtown area. He saw our interdependence, as well as the joy and love inside of people. So there’s a historical basis for that in our city.

When I talk about compassion it’s been tremendously well-received, not just in our community but all over the country. It doesn’t have any kind of borders politically, ethnically, or racially. I talk about it as a human value. And people who have a secular pulpit such as myself should be discussing the importance of human values like compassion, kindness, and love. Whether we like it or not, we’re in this together. We are imperfect people on an imperfect journey, but we need to get started with the journey.

Jennings: What was the reaction you received when announcing that you were making compassion a centerpiece of your governing? Was there any resistance or confusion?

Fischer: I think it was unexpected. Most people don’t expect a political leader to be talking about compassion. I believe my background as a business person gave me credibility to be speaking about how you build a great city. To build a great company you need the right skills, teamwork, and commonality of purpose. It’s the same with a city. Similarly, there’s no successful business that’s not a compassionate business, by which I mean that the businesses are interested in their employees’ potential flourishing. But the benefit for the employee is an increase in their human potential. So this spills over and it has a positive impact on their families, communities, houses of worship, and so on.

The first thing we started with was service projects, which were easy to do and easy to measure. That was expressed through our “Give-A-Day” week of service. Last year we had over 165,000 volunteers and acts of compassion during the week. We’ve had forty cities from around the world, benchmark our compassion efforts, so it’s definitely gotten people’s attention.

Jennings: What does it mean when you say forty other cities have benchmarked what you’re doing?

Fischer: We have the different constellations that focus on different elements of compassion, such as education, health, and business. They’re trying to understand work that we’re doing and compare it to the work that they’re doing.

Jennings: Are there other initiatives besides the “Give-A-Day” that are part of this push?

Fischer: I look at compassion now as a whole approach to our city. So we’ve got the “Give-A-Day,” we’ve got education components of that, and the Compassionate Schools Project is part of it. Dr. John Klein has introduced the idea of “Compassion and Healthcare” at the University of Louisville Medical School. In our Corrections Department, in our jail, they now are implementing mindfulness-based compassion practices with their staff. They’re working with Fleet Maul. We don’t have a list so to speak, but this thing has grown far bigger than me or my office. There are all kind of things going on around compassion that I don’t know about, which is great. The Festival of Faiths was, of course, an anchor. You should see the reaction the community had when one of our mosques was defaced several months ago. We had a press conference the next morning where we said, “This is unacceptable for our community” and invited community members to come the next day and help clean up the mosque. You and I could’ve cleaned it up in half a day or a day—just the two of us. Over a thousand people showed up.

Jennings: I would have loved to see that.

Fischer: It was a beautiful display of love and compassion. When we were there, you could feel the buzz around people about how they weren’t going to put up with this kind of thing and also their focus on interconnectedness and interdependence. I don’t know what Thomas Merton felt in 1958, but I felt that sense of interconnectedness at that event with the mosque.

The purpose of some of this work is not just the increasing of human potential but also the creation of social muscle. Every city needs social muscle because, inevitably, you’re going to have tragedies or setbacks. And the question is, “How do you respond?” Do people lash out at each other and make the situation worse or do you come together and try to move forward? So all this work we do in compassion has created a large group of people that come together at different times to do different things so that when we have challenges people are ready to step up.

Jennings: Let’s talk about the Compassionate Schools Project. What role do you see adults playing in helping our children learn compassion?

Fischer: Our children can’t reach their potential if they’re not able to see the world beyond a narrow lens. The challenge that we all face is that we all see the world the way we see the world and our set of experiences can either be limiting or broadening, depending on what you’ve exposed yourself to, what your curiosity toward learning is, and what your comfort level is being around people that are not like you. Adults that are interested in the maximum development of their kids will provide a variety of experiences for them. This doesn’t have to cost money, although if you have resources it’s easier to do that in terms of activities or travel. If you don’t, there are still all kinds of ways to do that in terms of interacting with different cultures or different faiths.

Adults are going to be the ones that are hopefully modeling this type of behavior. You don’t just a flip a switch and suddenly become compassionate. It might start with curiosity, saying, “I realize that if I believe in this notion of interdependence then I’ve got to understand who I’m interdependent with. What do I need to know?” You see that at the beginning of a lot of discussions people have around race relations and trying to understand what our next steps in civil rights are.

Jennings: How did Louisville become the site of the Compassionate Schools Project?

Fischer: Owsley Brown has been a fellow traveler on this compassion journey and said he wanted to help. After some deliberation we decided that we should start with education. Owsley’s relationship with UVA and your Contemplative Sciences Center was a perfect way to meld the interest in education, his love for his alma mater, and contemplation and mindfulness. This, along with the willingness and enthusiasm of Superintendent Donna Hargens here in Louisville, has led to the Compassionate Schools Project.

Jennings: How have citizens responded?

Fischer: At this point it’s not widespread all over the community because we’re just in three schools. When I talk to people who are familiar with the Compassionate Schools Project, they are uniformly enthusiastic. They may not understand what’s going on or why it’s going on but they might talk about the calmness of the classroom, how kids are able to cope better now.

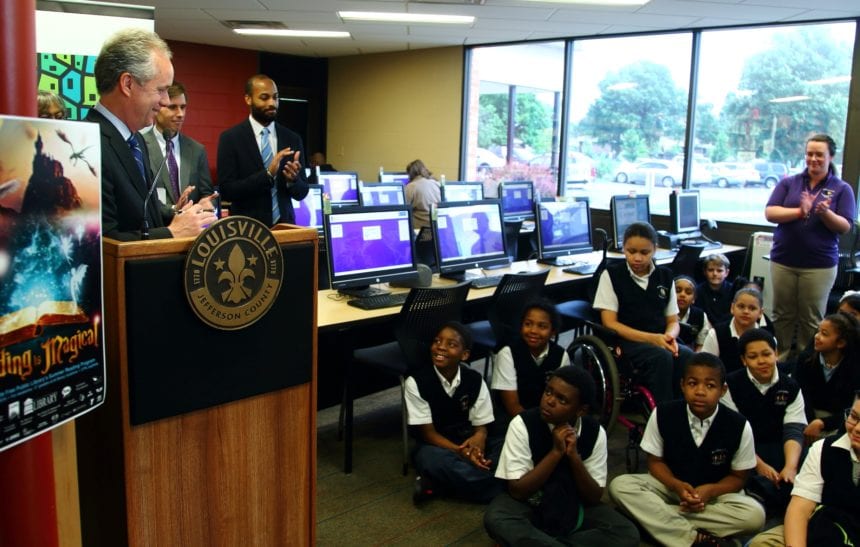

Jennings: When you’ve visited the classes, what was your perspective on what you were observing?

Fischer: The biggest impact on me was listening to the students talk about the program. It’s so exciting to see these young kids have these moments of insight about themselves, their communities, and families. Because that moment of insight is a door opening up to awareness and understanding that they never had before. It’s so powerful because when you open a mind, there are infinite possibilities. When you think about the power that can have both intellectually and emotionally for a student, it brings you back to the purpose of compassion in the city, which is enabling human potential to thrive. The challenge from there is making sure that stays intact and its nurtured.

Jennings: How can the Compassionate Schools Project curriculum help children in school?

Fischer: If we believe that this program is allowing them to be calm and have open minds and open hearts, then just the attention that they’re able to give to their school work and the meaning that school work has for them will be enhanced significantly. From there we can start to talk about how we are integrating the learning of these kids into more follow-up opportunities to become engaged citizens? I would certainly think that would be a byproduct of them starting to see that the world is not just about them, and that it’s about a broader picture of interdependence.

I often talk about citizenship and compassion in a complementary way. First, take care of yourself so you can take care of your family. Second, take care of your employer and vice versa so there’s a good relationship between the two. The third thing is to participate in and involve yourself in your community and do good things for which you expect nothing in return other than you get to live in this community and country. You can’t have a healthy person if you don’t have a healthy system and vice versa. A system can be either virtuous or negative. What I’m hoping with this curriculum is that we’re teaching kids that they’re part of something bigger. We have to start by each child recognizing the inherent goodness and potential that they have.