What is the Role of Laughter in Contemplative Practice?

By Alex TzelnicHere is a modern koan: two friends decide to meditate alongside a dog named Jules. It is immediately apparent that Jules is unsettled by the sight of two humans sitting completely still. She begins to nudge these humans; gently at first, and then with more insistence, as if to say, snap out of it! After a few restless minutes, Jules picks up a fur rug in her mouth, and viciously swings it back and forth, chunks of fur flying in all directions. “Jesus Christ!” screams Jules’ owner, rising to tend to the dog as the other friend erupts in laughter. Was there any wisdom to be gleaned from this experience, the friends later wondered, or was it a total waste of time?

This “koan” occurred at my bachelor party a few years ago, as my friend Sam and I bravely tried to balance the mindlessness of the weekend with a dash of mindfulness. I had met Sam on a Buddhist studies program in India in 2005. At one point during the semester a reputed Tibetan lama came to town to provide a week of lectures. One night, another student on our program raised his hand and asked, “Why do we laugh?” One of the lama’s followers, who later told me he was mortified by the simplicity of this question, quickly cut in to ask for clarification on a tricky bit of Nagarjunian philosophy. I have long forgotten the lama’s answer, but not the student’s question.

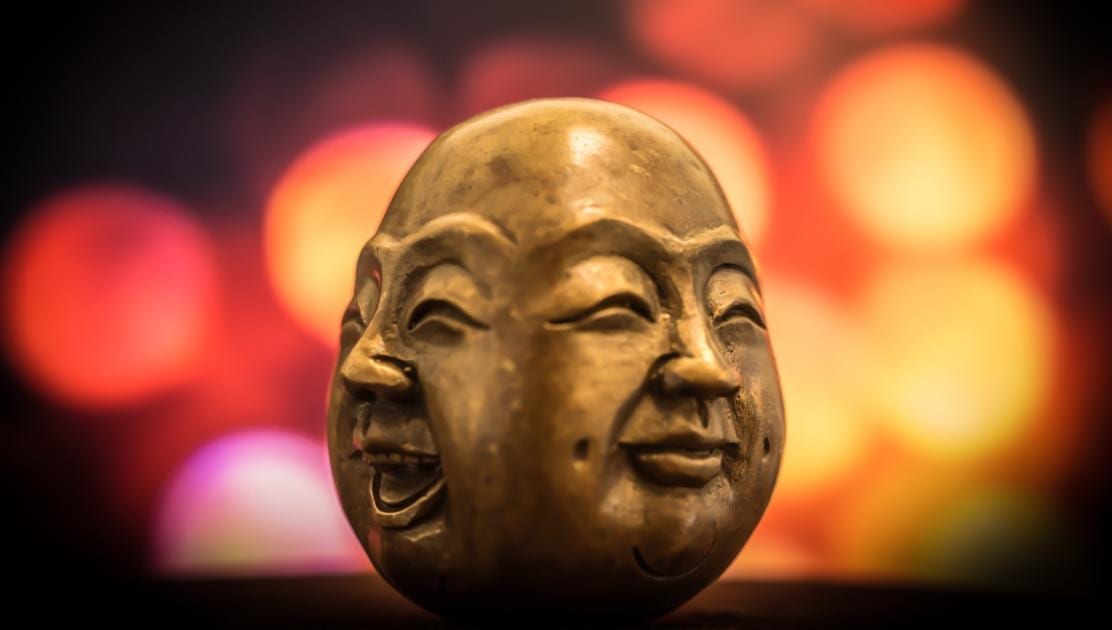

For some, like the lama’s follower, laughter might seem at odds with the purported gravity of contemplative practice. The Great Matter is birth and death, after all, not comedy. Yet Buddhist history is rife with merry pranksters and witty repartee. From the bawdy poetry of Ikkyu to the joyous songs of Milarepa to the tete-a-tete of koans, humor is baked into the tradition, part of the dharma in a fundamental way. But what purpose does it serve? Why do we laugh?

Many intelligent people have taken a stab at answering this question. The author Arthur Koestler once wrote, “In a good joke, there is a rupture of the logic, a point where the narrative departs from its natural flow and takes a sharp turn to the unexpected. That’s when we laugh.” The comedian Hannah Goldsby said something similar in her recent comedy special “Nanette”: “Let me explain to you what a joke is. When you strip it back to its bare essential components, its bare minimum, a joke is simply two things: a setup and a punch line. It is essentially a question with a surprise answer.”

Perhaps this helps explain why humor is so prevalent in Buddhism. Contemplative practice is, in a sense, a question without an answer (hence all the contemplation). It can sometimes feel like a bad joke, returning to the cushion again and again–setup after setup with no punchline. It’s a process that can often feel pointless, sometimes profound, and occasionally comical. But when we start to drift, or sink, or yearn, the immediacy of laughter can bring us right back to the present. The reminders, both in the canon, and in our day to day life, that we can laugh at the absurdity of it all can be liberating.

Delving into the absurd can often provide a unique opportunity for insight. Dr. Pamela Winfield, associate professor of Buddhist Studies at Elon University, points to the use of koan practice in Rinzai Zen as an example of this. The classic koan–if a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?–is not simply a question of dendrology. The idea, says Winfield, is to “deconstruct normal discursive, dualistic, discriminative thinking and absolutely shipwreck it up against the rocks of the question.” In the case of our fallen tree, the koan, Winfield explains, “automatically engages yet subverts our normal subject-object cognitive categories, and we are left unsure about both the perceiver and the perceived. This unsettling is the whole point; it loosens up the very ground of our being and opens up a little space for light and air and joy and spontaneity to come in.”

A little levity can also be crucial to the healthy functioning of a spiritual community. As anyone who has ever been on retreat knows, there is a special kind of mortification reserved for erring in a mindful space. If you bow at the wrong time in a totally silent and still room, it can make even the hell realms seem like a more appealing place to be, at least for the moment. “When someone makes a blooper in the liturgy we can yell at him or we can all have a good laugh together and no harm done,” says Randall Ryotan Eiger, sensei at the Village Zendo in New York. “The gentle laughter of a sangha softens the hearts of each member and creates a space for wisdom and compassion to arise, usually in invisible, precious, ordinary ways.”

Of course, this doesn’t mean that laughter is a cure-all that we can employ whenever we run up against the discomfort of uncertainty, and exploring that uncertainty can be just as important as maintaining a sense of humor. Ultimately, laughter is simply an expression, and like any expression it can be directed in manifold ways. “We laugh because we’re human,” explains Eiger. “The same reason we sing, dance, belch, or go to war.” But in practice it can be an immensely useful expression, one that can signify compassion and even understanding.

“In the end, I suppose Buddhist humor is like any humor,” says Professor Winfield. “It’s designed to shine a light on existence so that we can see it in a new and refreshing way. It snaps us out of our humdrum neural grooves and opens up a wonderful and wondrous space for play. This is why my criteria for judging any enlightened person in any religious tradition is seeing if they can laugh at themselves and the world.” Eiger would agree. “Probably the healthiest laughter,” he says, “is the laugh we have on ourselves.”

What I remember most about that sitting round with Jules is the way Sam and I, in the aftermath, repeatedly failed to regain our composure. Jules was like a physical manifestation of our minds, nudging our attention this way and that, eager for distraction. As we attempted to continue our practice, one or the other of us would start to crack, triggering another round of helpless laughter. So, was there any wisdom to be gleaned from this experience? It’s hard to say, but it opened up a little space for light and air and joy and spontaneity to enter into our practice.

Alex Tzelnic is a writer and Zen practitioner living in Cambridge, MA.

Photo by Mark Daynes on Unsplash